Starmer’s Sham Crackdown: Britain Still Wide Open to Chaos

Labour says it’s getting tough on immigration crime—but with prisons bursting and justice broken, is this bold action or just another cowardly con?

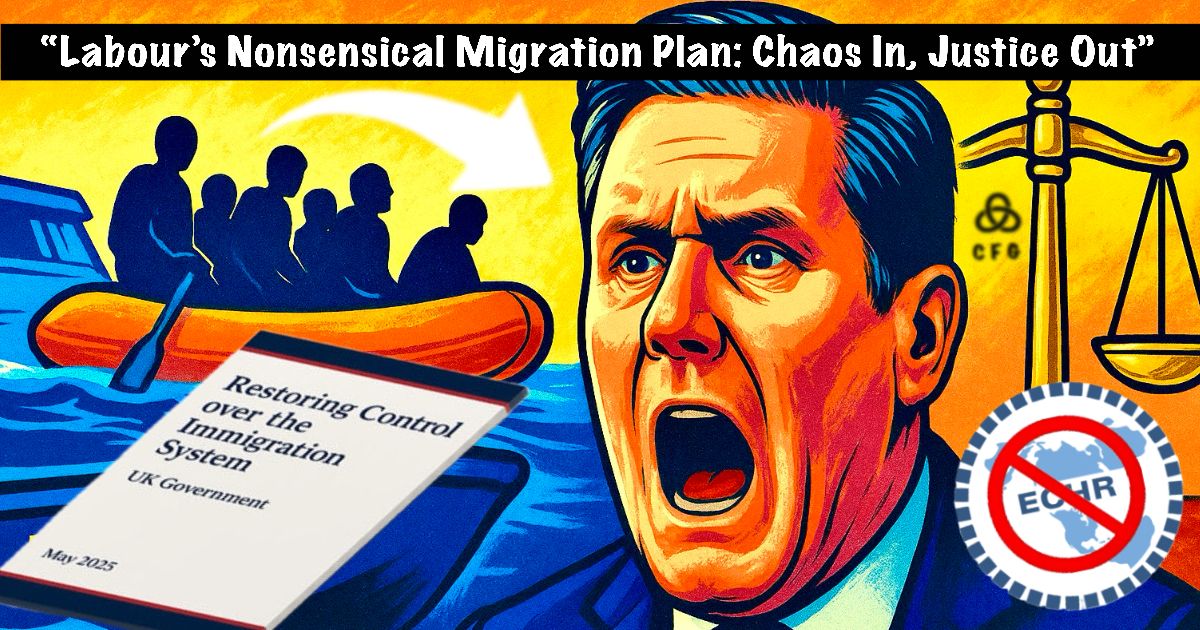

In the grand theatre of British immigration policy, the latest act has arrived not with a bang, but with a convertly clenched jaw. Prime Minister Keir Starmer, delivering a statement that one suspects lodged somewhere deep in his throat on its way out, has finally declared that unchecked mass immigration is, in his own words, a “completely failed social experiment.”

An admission many said they’d never hear from Labour lips—less a U-turn and allegedly more a full emergency stop. And yet, now that it’s been said, it cannot be unsaid.

Starmer’s sudden Damascene conversion to immigration realism marks a moment of rare agreement between all major parties. The once-taboo is now gospel: mass, unskilled immigration has corroded the economy, strained the infrastructure, and, as the Prime Minister himself put it, turned us into:

“An island of strangers.”

If those words sound familiar, it’s because they eerily echo the famous phrasing of Enoch Powells "Rivers of Blood" speech. Though completely lacking Powell’s poetry and venom, the sentiment is dangerously adjacent. And once uttered, these things stick like legal precedent.

But rhetoric is easy—White Papers are harder. The 2025 policy document, “Restoring Control Over the Immigration System,” is being paraded as the blueprint for a bold new order. On its face, it is a manifesto of finality, a promise that the UK will at last take back control of who enters, who stays, and crucially, who gets shown the door. Yet when examined through the cold, sober lens of the law—and it must be—the entire paper reads less like a plan and more like a legal Potemkin village: façade in front, collapse out back.

Take for instance the proposed restriction of Article 8 of the European Convention on Human Rights, that well-trodden clause granting the right to respect for private and family life. Labour suggests that “clarifying” this right will prevent its misuse in deportation appeals.

But there’s a catch: Article 8 is already a qualified right. The courts can—and do—intervene where national security or public safety demands it. This isn’t reform; it’s rebranding. A false solution to a problem that is already addressed in existing statute and case law. The legal equivalent of putting a new label on an empty tin.

Moreover, even if Article 8 were entirely set aside, the next legal redoubt—Article 3, the prohibition on torture or inhuman or degrading treatment—is absolute. No government can derogate from it. So if an asylum seeker faces risk of mistreatment on return, no amount of domestic White Paperery will override that obligation. This is international law, not wishful drafting. Once again the only way to deal with these issues in any meaningfully effective way is to leave the ECHR!

And yet, the real crux of this policy paper—what makes it politically allegedly seismic—is not just in its legal tangle, but in its collision course with the justice system. Labour’s claim that foreign criminals will be automatically deported upon conviction is as much a confession as it is a commitment. It tacitly admits what those of us in the courtroom press-galleries have known for some time: the system is broken. Not just bruised. Broken.

The judiciary is on its knees. Not metaphorically. Literally. With over 88,000 people incarcerated and only around, 1000 available spaces, our prisons are operating at what officials are now charitably describing as “emergency threshold.” In plain English: there’s no room at the inn. We are at crisis point, with no viable plan to build the necessary infrastructure in time to catch the inevitable overflow. Judges and Magistrates are quietly handing down suspended sentences and community orders where custodial terms are actually merited, not because of leniency, but because there is literally nowhere left to put them. If ever there were a moment to stop talking and start acting, this is it.

And here, the White Paper conspicuously omits what could have been a pragmatic approach. The notion and concept that we must commute the prison sentences of foreign nationals—nearly 11,000 of whom are currently occupying UK prison cells—to immediate deportation is not radical. It is, frankly, overdue. Deportation in lieu of incarceration is not a moral question; it is a logistical necessity. We do not have the concrete, the manpower, or the time to build our way out of this. What we do have is an overpopulated prison system, and a judiciary with no deterrent left to wield.

This policy, if enforced without apology or equivocation, could go some way to restoring a semblance of function to the criminal courts. Once at least some of those 11,000 beds are cleared, the judiciary can resume what it is supposed to do: punish crime, deter reoffending, and restore public confidence. But for that to happen, the policy must be enforced without fear of offending the sensibilities of Labour’s new inner-city voter base—those urban, professional, latte-liberal types who prefer to tweet about equity than stomach the dirty business of enforcement.

There is a quiet irony here that no-one in Westminster seems quite ready to confront. For years, critics warned Labour that its open-border policies were alienating traditional voters. And now, in a bid to recover those voters, the party finds itself drafting immigration language that could have come straight out of a 2004 Conservative conference. And yet, it is still unclear whether Labour is prepared to actually implement the measures it now claims to champion. The risk of upsetting Islington’s brunch crowd may yet outweigh the urgency of securing Britain’s borders or restoring its legal order.

Of course, the rest of the White Paper doesn’t fare much better. The proposed hike in residency requirements for Indefinite Leave to Remain—from five to ten years—is unlikely to survive the scrutiny of any competent judicial review. Nor will the expanded visa revocation powers, which suggest the Home Office could cancel visas on the basis of criminal activity not even resulting in imprisonment. On what evidence? Under what burden of proof? With what safeguards? Silence.

Similarly, the changes to the skilled worker visa system—raising both salary and English-language thresholds—may achieve nothing except to bar lower-wage but essential workers from entering legally, while doing nothing to stem illegal arrivals. You can raise the salary bar all you like, but it does little to deter someone crossing the Channel in a dinghy with no documentation at all.

And all of it sits atop the central fiction that immigration control is primarily a matter of domestic willpower. It isn’t. It’s an international legal construct, layered over with ECHR obligations, UN conventions, human trafficking statutes, and cross-border treaties that can’t simply be torn up at the next press conference. Domestic politics can’t abolish international law. Yet still the fiction is maintained. Because it sells.

In the end, the 2025 White Paper may be most notable not for what it proposes, but for what it reveals: a government now belatedly admitting what the public has known for a decade—that the system has failed. It has failed to control borders. Failed to deliver justice. Failed to protect the rule of law. And now, as a final indignity, it appears poised to fail at fixing itself, too—crippled by internal contradictions, legal impracticalities, and a party still terrified of offending its own base.

But the clock is running out. Without immediate action—real, legally defensible, and ruthlessly enforced—the UK faces not just an immigration crisis, but a full-blown judicial collapse. In that context, deportation is not cruelty. It is triage. And if Labour truly intends to govern, it must now decide whether to prioritise performative empathy, or institutional survival.

Well, that’s all for now. But until our next article, please stay tuned, stay informed, but most of all stay safe, and I’ll see you then.